ANDREW'S LIFE STORY

EINLEITUNG (F.K.)

Ich lernte Andrew im April 1973 einige Tage nach meiner (ersten) Ankunft in Sandema kennen, und zwar stattete er mir in meiner derzeitigen Unterkunft, dem Sandema Resthouse, einen Besuch ab. Andrew war arbeitslos. Er wusste zwar, dass er für die neu eingetroffene presbyterianische Krankenschwester (Sister Dorothy) wieder arbeiten konnte, es fehlte jedoch noch die offizielle Arbeitserlaubnis und der Landrover für die Mobile Clinic. So bot mir Andrew, der schon 1967-68 für Herrn Prof. R. Schott in Sandema als Informant und Helfer gelegentlich gearbeitet hat, seine Dienste an. Da ich selbst noch malariakrank war und auch schon einen anderen Assistenten hatte, konnte ich von seinem Angebot zunächst kein Gebrauch machen. Andrew machte eine resignierende Bemerkung: er komme im Leben immer zu spät.

Ich traf Andrew wieder bei einer großen Totengedenkfeier in Sandema-Kalijiisa-Choabiisa. Er befand sich in der Schar der Musiker und schlug eine große Zylindertrommel. Als am Spätnachmittag sich der Großteil der Festgesellschaft, voran die Musiker, in einer Prozession auf den Weg zu einem heiligen Hain (tanggbain) machte, um dort rituelle Handlungen vorzunehmen, gab es plötzlich eine Stockung. Einige ältere Männer berieten sich und baten dann Godfrey Achaw und mich, zum Gehöft zurückzukehren. Aber auch Andrew durfte den heiligen Hain nicht betreten, obwohl er eine öffentliche Funktion als Trommler ausübte. Später erklärte man mir, dass es keineswegs ein generelles Verbot für Christen gäbe, ein tanggbain zu betreten, denn in der Festgesellschaft befanden sich noch mehrere Christen, und auch ich selbst habe das tanggbain später mehrmals besucht, Man erwartete jedoch von den abgewiesenen Personen spöttische Bemerkungen oder fühlte sich zumindest durch ihre Anwesenheit gestört.

In den folgenden Monaten sah ich Andrew häufiger auf dem Markt von Sandema. Er war fast immer nach europäischer Art mit langer Hose und weißem Hemd bekleidet, mitunter trug er jedoch auch den traditionellen Männerrock (Buli: garuk, engl. smock). Ich stellte fest, dass er ein starker Raucher ist und sehr gerne und häufig Kola-Nüsse isst. Fast immer hatte Andrew auf dem Markt noch Nebenaufgaben zu erfüllen: er sammelte Gelder für die presbyterianische Pfarre ein und führte Botengänge für den Sandemnaab (Häuptling von Sandema und Oberhäuptling der Bulsa) aus. Hiervon abgesehen lag der Schwerpunkt seiner Arbeit in der Bebauung seiner Felder, die er von seinem Onkel (MuBr) in Kalijiisa erhalten hatte.

Seit Juni 1973 erhielt Andrew kleinere Aufträge von mir. Schriftliche Berichte über Übergangsriten zeigten, dass er keine besonders guten Kenntnisse über die traditionelle Religion und ihre Riten besaß. Übersetzungen aus der Kasem-Sprache führte er jedoch zur vollsten Zufriedenheit aus. Auch von den Angestellten der Presbyterianischen Mission Sandema wurde Andrews außergewöhnlich sorgfältige und gewissenhafte Arbeit immer gelobt.

Sein guter Kontakt zu den Kasena (besonders zu dem Dorf Chana) und seine Beherrschung der Kasem-Sprache kamen mir ein zweites Mal zustatten. Zusammen mit ihm besuchte und interviewte ich in Chana-Katiu eine Frau, die Mädchenbeschneidungen durchführt. Dieser Besuch hatte jedoch ein Nachspiel. Nachdem bei Beschneidungen in Wiaga zwei Mädchen in der Trockenzeit (1973/74) gestorben waren, glaubte die Frau, die Schuld liege am Besuch des Weißen Mannes. Sie suchte Andrew auf dem Markt auf und beschimpfte ihn vor allen Leuten, weil er ihr einen Europäer ins Haus gebracht hatte.

1974 bat ich Andrew, mir seine Lebensgeschichte aufzuzeichnen. Seine Reaktion war außergewöhnlich. Er sagte mir, dass er so etwas immer schon vorgehabt hätte, da sein Leben neben Erfolgen besonders viele harte Schicksalsschläge erfahren habe. Er erwähnte sofort, dass er ein Mädchen, das er sehr geliebt hatte, nicht heiraten konnte, dass sein Vater seine Schullaufbahn zerstört und man all seine Bücher und Kleider in Sandema gestohlen hatte.

Nachdem ich von mehreren Bulsa-Schülern sehr kurz gefasste Lebensgeschichten erhalten hatte, die nur die wichtigsten Fakten ihres Lebens enthielten, machte ich Andrew darauf aufmerksam, dass er in seiner Lebensgeschichte auch Gefühle, wichtige Gespräche, Meinungen usw. aufzeichnen könne. Schon nach einigen Tagen erhielt ich die ersten Seiten seines Manuskripts mit der Frage, ob er so weiterschreiben könne. Nachdem dies bejaht worden war, erhielt ich fast jede Woche einen Stoß meistens bis zu den vier Rändern in kleiner Schrift vollgeschriebener Seiten. Als Schlussteil seiner Lebensgeschichte überreichte er mir die Aufzeichnungen über die Folgen des Kleiderdiebstahls.

Kurze Zeit später erfuhr ich von anderer Seite, dass Andrew vor einigen Jahren große Schwierigkeiten gehabt hatte, da er unbedingt ein Haus mit Blechdach in Kalijiisa-Anurbisa bauen wollte. Ich bat ihn daraufhin, mir diese Begebenheit aufzuschreiben; dieser Bericht umfasst das Kapitel IX .

Die Ausführungen über die Erziehung seiner Kinder wurden auch als eigenständige Arbeit verfasst und von mir als 10. Kapitel angegliedert.

Nach der Fertigstellung der Life-Story und ihrer Ergänzungen erhielt Andrew von Pastor James Agalic seine Anstellung als Evangelist in Chana. Ich bat Andrew, sich tagebuchartige Notizen über seine Tätigkeit dort zu machen, um später einen weiteren Ergänzungsbericht zur Lebensgeschichte anfertigen zu können. Der fertige Bericht (Kapitel 11) mit einigen erlässlichen Wiederholungen spiegelt in seiner streng chronologischen Fassung noch stark den tagebuchartigen Grundplan wieder.

Während meines einjährigen Forschungsaufenthalts 1988/89 in Wiaga, hatte (zufälligerweise) auch Herr Prof. Schott mit seinen damaligen Assistenten Barbara Meier und Martin Striewisch einen einjährigen Aufenthalt in Sandema geplant, um sein Erzählforschungsprojekt fortzusetzen. Andrew kam häufiger in ihren “Compound”, hat wohl auch schon einmal kleinere Arbeiten für sie ausgeführt, gehörte aber wohl nicht zu den Hauptmitarbeitern oder -informanten. Eines Tages vermisste einer der deutschen Ethnologen ein teures Feuerzeug. Da es mit Sicherheit kurz vorher noch auf einem Tisch gelegen hatte und nur Andrew zu einem Diebstahl Gelegenheit gehabt hätte, warf man ihm diesen unverblümt vor. Nach kurzen Ausreden gestand er die Tat und gab das Feuerzeug zurück. Danach kam einer seiner etwas jämmerlichen Auftritte. Er weinte und sagte, dass Gott ihn für seine Tat bestrafen würde.

Später hörte ich, dass er einen Schlaganfall gehabt hatte, und als ich bei meinem Aufenthalt 2006 (?) in Sandema nach Andrew fragte, erfuhr ich, dass er gestorben war. Eein Sohn lebt noch in Sandema.

Während Andrews Aufzeichnungen in ihrer grammatischen Struktur und Idiomatik weitgehend eine Anwendung der englischen Sprache, wie sie in Ghana gesprochen wird, demonstriert, weisen seine Niederschrift in orthographischer Hinsicht starke Mängel auf, was ihm durchaus selbst bewusst ist. Einige Wortschreibungen sind fast nicht in ihrer Bedeutung zu erkennen (Gunne Firwles = Guinea fowls; thusueruers = trousers; defrinces = differences).

Stilistisch erreicht die Lebensgeschichte an mehreren Stellen eine romanhafte oder in ihren Dialogen dramenartige Darstellungsweise, wie sie sonst in keiner Lebensdarstellung von meinen anderen Bulsa-Schreibern anzutreffen ist. Gedankliche Abschweifungen werden durch Assoziationsreihen gerechtfertigt: Als er hungrig in Kumasi erscheint, muss er an seine Freundin denken, weil sie ihn früher mit Nahrung versorgt hat. Präzise Wiedergaben von Gedanken oder Gebeten, die viele Jahre zurückliegen, exakte Angaben von Daten, Wochentagen (sie können nicht immer stimmen), Uhrzeiten, genauen Preis- und Maßangaben (z.B. Rast am 6. Meilenstein; 24 ccs penicillin; die genauen Abfahrtszeiten des Busses usw.) gehören zu Andrews außergewöhnlichen Darstellungsmitteln. In der Angabe der Jahreszahlen sind ihm jedoch offensichtlich einige Fehler unterlaufen (Neuvorschläge in eckigen Klammern).

Typisch für die Erzählkunst der Afrikaner ist eine gewisse Breitschweifigkeit. Wenn eine Person auf ein vorher beschriebenes Ereignis hinweist, so wiederholt sie alle Einzelheiten des Ereignisses noch einmal (s. zum Beispiel Ende des Kapitels "Running away to Tamale and Kumasi"). Stilistisch besteht ein Unterschied zwischen dem ersten Teil (der in einem Stück angefertigten Lebensgeschichte) und den beiden später erstellten letzten Kapitel. Während er anfangs noch kurze Sätze benutzt und die Handlung relativ rasch voranschreitet, nehmen Wiederholungen und eine starke Weitschweifigketi in den beiden letzten Kapitel in starkem Maße zu.

Obwohl Andrew Interesse an einer Aufzeichnung seines Lebens hat, schreibt er doch in erster Linie für den Ethnologen (F.K.), den er an einer Stelle der Lebensgeschichte sogar mit Namen anredet (Dear Mr Kröger...).

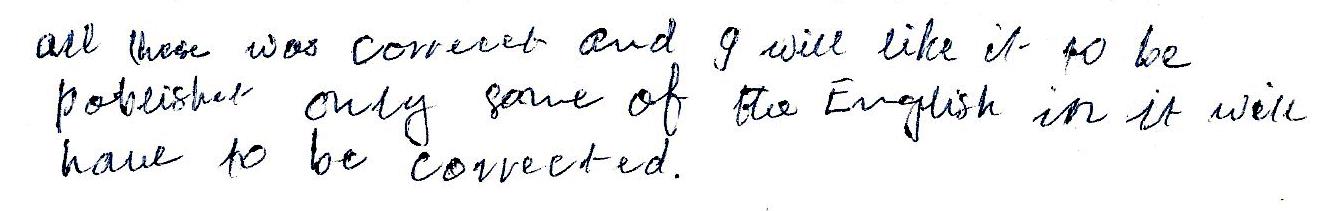

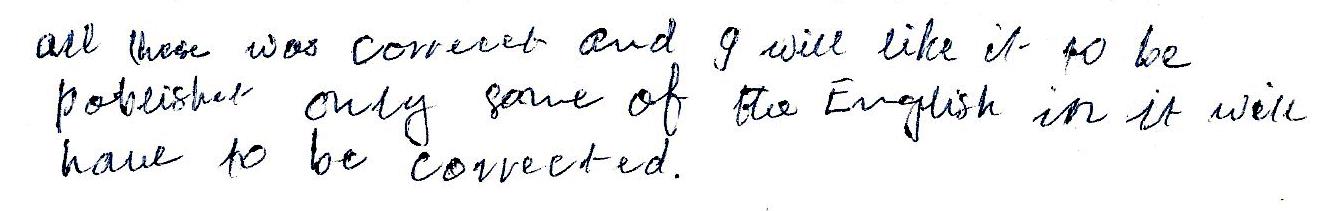

Eine Veröffentlichung als Aufsatz- oder Buch (das Internet bestand damals noch nicht) begrüßt er ausdrücklich:

Direkt auf die Frage angesprochen, ob er anonym (bzw. mit einem veränderten Namen) in der Lebensgeschichte auftreten wolle, entschied er sich zuerst für die Anonymität. Später sagte er mir jedoch, ich könne seinen richtigen Vornamen ruhig verwenden, da es allein in Sandema mehrere Männer mit diesem Namen gebe. Ich (F.K.) habe mich hier trotzdem für eine Namensänderung entschieden. Die Ortsangaben und die Namen anderer Personen in der Publikation entsprechen allerdings genau den von "Andrew" genannten.

Um die Lesbarkeit zu gewährleisten habe ich Andrew's Orthographiefehler weitgehend verbessert. Die dem Schreiber eigentümliche Stilistik, die dem Werk seinen spezifischen Charakter verleiht, habe ich nur dann verbesser oder in eckigen Klammern eine korrigierte Version angefügt, wenn es für das Verständnis notwendig war.

LIFE STORY

CHILDHOOD IN SANDEMA

I was born at Balansa in the year 19441. I was the 5th birth of my mother. Her first born was a boy who was our elder brother. He died at the age [of] about seventeen. I was told [about it], I cannot remember well about that.

My mother took me to her father's house because of some quarrel between her and my father2. That was when I was about three years old. She did not go back to my father before one year staying with her father. [Then] my father paid a visit to his father-in-law asking to send back his wife and son to him. So I was told by my father when my mother went back together with me to him.

In 1949 there was a force [law?] by the Sandemnaab that every child about five years old or over should go to school3. He [the Sandemnaab] sent out the then Local Authority Police to go round all the Bulsa District [to look] into the compounds to find out children [of] about the age of five or over and bring them to school. If their parents refused to send their children to school, the L.A. Police should bring them before the Local Court4. My parents got to hear of this news and asked me to go to my uncle's [mother's brother's] house. By then I was five years old. So I went to my uncle's house5. I stayed there for three years. The police came there to look for other children in the house. They did not see me, because my father told my uncle not to let me go to school. And so, when the police were coming to the house, my uncle asked me to go to the bush6 so that the police could not see me around the house. So I went to the bush in the morning and came back in the evening. By then the police had gone away with some children from that area.

While I was there [at my uncle's] my father and mother paid a visit to me asking me whether I was all right there or not. My answer to these questions was always: "Yes I am o.k. here." They told me to get the tribal marks7 on my face, and I refused to do so.

At my uncle's house there was a very beautiful girl. She loved me and I loved her also. So always in the afternoon the two of us dah [used?] to go far away from the house to a tree to sit under it. It was about 100 yards away from the house. There we used to play. This girl came from Chana together with her father. The kind of play we were playing was all about love. She was teaching me how a boy could have a girl friend and how she had been watching her father the way he loved his wife8. She said to me that she would like to marry me. As I really loved her, I said: "Yes, I do love you. But only I am still a very small boy, and so my father may not agree that I should marry at this time."

And so one day in the afternoon we were sitting under the tree talking about the tribal marks, and there came a man from Chana. This man was the cutter of tribal marks9. Then the girl called him to come. When he came, she said to him: "Look, here is a boy without the marks. His parents have been asking him to do the marks, and he would not agree because of fear." Then the man asked me: "Is it true?" And I said: "No!" The man then said: "Would you like to get it [them] now?" I wasn't going to agree, but because of the girl's presence here I thought: If I don't do it, she may say that it is really true that I fear the painful cutting. So I answered: "Yes". So the man said to me: "Sit down and don't fear. I will make it small, so you will not feel the pains." So I sat down, and he began to cut me.

One week after the cutting on my face I said to the girl: "I will go to see my parents at Balansa and come back in two days' time." She agreed that I should go and come [back]. I went to my father. When he saw me with the marks, he was very happy. Also my mother was happy, because they were asking me to do the cutting of the marks and I did not agree10.

RUNNING AWAY TO TAMALE AND KUMASI

At my father's house there were two school boys. They were speaking English, which I didn't hear [understand] and when I asked them: "What are you saying?" they stared to insult me: " If you want to hear [understand] English, you must go to school11." At this saying to me I was worried and decided to go to school, but I thought: Maybe my parents will not agree. Or, if they will agree to let me go to school, I will not get the girl. There arose so many thoughts in my mind , and at last I thought I had to go to Kumasi12. And if the girl hears that I have gone to Kumasi, she may like to join me there. I went into my father's room and began to search for money there. I found the money: then 15 Gold Coast Pounds13. It was about 3 o'clock p.m. in the afternoon. I thought, if I take the money now and my clothes going away [having disappeared], they may know [that I have gone away]. So I have to wait until it is dark, when they can't see somebody walking along the road. Then I will go in to take the money and go away to Kumasi. This decision was not succeeded [successful]. At night I went into the room for the money, but I couldn't find it, where it had been, only nine shillings were there. By then I had prepared and was ready to go. But though I could not get the 15 [pounds], I thought that I must go today even with this small money [of] nine shillings.

So I took that money and went, but from Balansa to the town [Sandema]14 is about three miles. So I walked to the town. That time, when I left my father's house going away to Kumasi, it was about 4 a.m. There were no lorries in Sandema at that time15. So I had to walk on foot to Navrongo [28 km]. I was at Navrongo round about half past six. There I got a lorry [lorry of bus] going to Bolga. The driver charged me 2 shillings. We reached Bolga about 7 a.m. From Bolga I joined another lorry to Tamale. 5 s. was the charge from Bolga to Tamale. I met young Bulsa men at the lorry station. They were servants to the police16. They asked me where I did come from, [and] which part of Bulsa I did come from. I said that I did come from Balansa. They said that if I wanted a job, they would get me a job. I said: "Yes!". So they took me to the Police Station, and one of the policemen employed me to look after his horses: washing them and to get grass for them every day, with the salary of 10s. [per month], the then Gold Coast Money.

I worked with him for only one month, because all my mind was to go to Kumasi. At the end of the month he paid me and I went away. I did not even tell him that I would leave him and the job. When I left the Police Station going to the town to get a lorry to Kumasi, I thought if I mean to take a lorry from the town, my master may see me and take me back.

So I walked a few miles from the town to milestone 6, Tamale Kumasi Road [i.e. 6 miles from Tamale] to join a lorry to Kumasi. The lorry's fee to Kumasi from Tamale was 6s. So from my salary of 10 s. only 4 s. were left with me, and I spend 1 s. on the way. We arrived at Kumasi very late in the night, and as a newcomer I did not know where to go , when I came down from the lorry. So I had to sleep in the lorry alone. The other passengers had all gone away. The next morning I awoke and stepped [out] to ask some people about my relative in Kumasi. Nobody could tell me, whether they knew any of them, because of the language [Twi], [which] I couldn't speak well at that time. I could only speak Hausa17 just a little. So the people of Kumasi speak only Twi.

I was wandering about this. God [was] so good [that] he directed me to a Frafra18 man, who spoke Hausa and Buli. So I asked him whether he knew a man called Asibi staying at Kumasi-Aboabo19, two miles away from Kumasi [centre]. He said: " Yes!". He questioned me: "Are you a Bulsa boy?" - "Yes!" I answered. He said: " Then come with me, and I will take you to his work side, because he will not be in his house now." So I followed him. We walked for a few yards. He asked me a question: "Have you eaten something this morning?" - "No," I answered him. "Do you want a roasted plantain?" he asked me. "Yes", was my answer. At that time I did not know a plantain20. I had only heard of it. So he went and brought some for me to eat, before he would take me to my relative. I sat down to eat. He again went and asked for water for me to drink.

All this kindness to me [made me] recollect the love of my girl friend, whom I left at home. I began to think of her love towards me at home. She would not eat her food until she saw me. And under the tree where we used to sit and play she would ask me: "Do you want some water to drink?" Or if I said to her: " Let us go home!" she would ask me: "Why? Are you so hungry?" And if I answered: "Yes!", she had to run quickly home to bring me something to eat from her mother with some water.

After I had finished eating that plantain, I got up and followed him [the Frafra man]. We came to the work place of my relative. He saw me and said: "Ha! Where do you come from? You small boy like that! You did escape from your parents! ah!" And [he] put his hands on my head with laughing21. The Frafra man laughed too, and said to my relative: " I saw him at the Lorry Station this morning. He was wandering about speaking half Hausa to the passers [by], but nobody could hear [understand] him. So I asked him: 'Are you a Bulsa boy?' He said 'yes'. He asked whether I knew his relative, Asibi by name, staying at Kumasi-Aboabo. I answered him 'yes', but knew he was not at home just now [then]. 'He will be at his working place. So come with me and I will take you to him'. And he followed me. So here you are! I brought your son to you." He said to him this way. My relative thanked the Frafra man and I said to him: "Please, thank him again, for he saved me from [getting] lost, and he also bought a plantain for me to eat, and I ate it and was all right." Asibi laughed. He thanked the Frafra man again, and the Frafra man said: " No, don't mention it!" And he went away.

GOING TO SCHOOL AND WORKING AS A HOUSEBOY

At 12 o'clock my relative took me home. His wife fetched me water to bath. She prepared food for me too. At 4 p.m. the man, my relative came home from his work and started to ask me about home news. I told him all the news from home and about school; how my parents did not allow me to attend [school].So he said that there is a White Man here. They are Fathers of the Roman Catholic Mission having a school here. [They] take children, no matter whatever ages they would be. "If you want, you can attend their school. They don't charge anything. So you can attend that school. I will take you there tomorrow. It is at Asawasi, near here." I agreed. The next morning he took me to the place and introduced me to the White Man. He was a very tall man with a beard. He accepted me and asked my relative what kind [of] language I spoke. My relative said: "Only half Hausa!". The White Man said: " No matter! He will soon understand Twi and English." And my relative went away.

That was in May 1950 [1951? 1952?]22. I went into the class with other boys. The teaching was [in] Twi; and for the higher class [in] English. In one month's time I began to speak English and was able to answer some questions. My teacher was an Ashanti man. He liked me very much. After class he would take me to his house and give me some of his food. Always I had to wash his clothes and iron them for him23. He was teaching me at his house, too. He was very good to me and bought a school uniform for me. Only his wife was bad to me, and [every] time he gave her money to be given to me when he left the house going to some place, the wife would not give me the money.

On one Saturday he was going to Takoradi. He asked me not to go to my relative either for food for he had left some money to his wife to buy food for me. So I should wash all the clothes and iron them, and the clothes were many together with his wife's clothes. Cleaning of the house was my job to do. So at first in the morning I had to clean the house. That was only on Saturdays and Sundays. When my master left for Takoradi I started to clean the house. I did not take breakfast at all, before I went to the pipe to wash the clothes. I finished at about one o'clock p.m. and came home. When the wife saw me, she said she was going out, and so I should start ironing the clothes that have dried. She would come back very soon. She did not give me any food to eat or money to buy food by myself and I was very hungry. So I decided to go to my relative to get some food. I went there. I did not meet anybody at the house of my relative. I came back [and] started to do the ironing of the washing. I was very tired and too much hungry. At about six p.m. my master returned back from Takoradi. I saw him coming, so I ran to collect his suitcase from his hand. He looked at me and said: "Jack24, what is wrong with you? You are looking with an anger [in your] eyes." - "Nothing wrong with me, sir!" - "Are you sick?" - "No, I am not sick, sir !" I collected the suitcase from him and he was walking ahead of me to the house. The wife had also returned back.

My master asked me again: "Jack, are you sick?" - "No, sir! I am not sick," I answered. "Then, what is wrong with you? Is it because I detained you from going to your relative that made you so sad?" - "No, sir!" was my answer. "Are you hungry then?" - "Yes, sir!" - " Did you not eat some food?" At this question the wife was looking at me with [an] unhappy face thinking that I might tell my master that she did not give me something to eat, and he would be angry with her. The master asked her: "Did you not cook any food today?" - "I did cook, but Jack was at the pipe doing the washing. He did not come in time, and I had to give his food to somebody. I thought he might have gone to his relative." - "What nonsense! I gave you money extra to buy food for him. Why did you [not] give him the money to buy something at the pipe side. You know that the clothes were many and that [it] will take [a] long time to finish."

He called one of his sons, by name Kwabena. "Come here!" When the boy came, he got up and went out with the boy and asked him: "What is your mother thinking about Jack? Is she always kind to him during my absence from the house?" Then Kwabena said: " No, she never gave him the money which you always left with her." Then my master asked me, if he [should] find some job for me to be done in the evening after school. "Will you do it?" I said: "Yes". He said: "That is good! You are a good boy and my wife is always unkind to you. So if you get a job for yourself, it will help you to get some dress and food to eat."

So the next morning he took me to a White Man, a Syrian25, by name Mr. Bayackly. He employed me as a steward servant to the club known as Syrian National Club of Gold Coast. My salary was 4 pounds (8 Cedis) a month. I had to start at 5 p.m. and close at 9 p.m. Some times later than that in fact I was very poor in the school.

All the time I did not forget of my girl friend at home. I wrote to her26, but there was no reply to me to know whether she was still at home and keep on the love [she] had had for me.

After school I had to go to my work at the club, that was 1950 [1951? 1952?]. [From] my first month's salary I posted 2 [pounds] to my father and mother. I said to them in my letter that I was attending school here in Kumasi, and so I did not know when I should come home. My father replied me saying that he had found a girl for me27. So I should stop the school and come home for the girl. I told my master, the teacher, about what my father wrote me, and he said: "No, that was no good idea!" I should try to complete my Middle Form 428 and find a better job before I could get married. In the school all the other boys hated me, because the master loved me more than them. So when any examination came and I failed, he had to correct me. I failed the form one exam and he, the master, pushed me through the history of [the] Gold Coast and the first kind [kings?] of the Ashantis. I failed all that in form one. I went to form two.

It was at this time I was employed by the Syrian man in the club. And at that time life was better for me, because I was earning some salary.

MARRIED AT THE AGE OF TWELVE

In 1952 [1956?] my father wrote a letter to me again asking me to come home. In the same year I heard that my girl friend had married somebody at Navrongo. I was very sad to hear this.

In 1956, at the beginning of August, my [Ashanti] master left for the United Kingdom. Before he left he gave me 20 pounds and a watch and many dresses. And above all he advised me to try and complete the Middle form Four, so that when he came back, he would find a better job for me. I should try to be patient with my class mates about their behaviour on me. And as for my father's advice, that I should marry, I should not take that kind advice, because I was still very young and also I had no good income for that. He advised a lot on good [?] life. I cannot remember all the advice he advised me. His last advice and question to me was that: "Is your father very old and has he other sons beside you?" - "No, he is not very old," was my answer," and he has other sons and daughters, but I am the son that he loved more than the other sons, my brothers and sisters29."

Then he removed 5 [pounds] from his pocket and two blankets from his box and gave them to me with the money [20 pounds]. "Here are some presents for your father! You can send them to him. Tell him the truth that you will not marry at this time, until you have finished your school and found a job, before you can marry. After this he parted [?] with [from] me and said: "Bye-bye, my boy!" I began to weep with tears, as he was going away, and I thought: I can't see him again.

I went back to his house to take my box and go to my relative. On my way home [to my relative] I was thinking: I have to go home to my father and mother before I come back when school has reopened. I thought again: What about if I go home and my father forces me to marry? What shall I do then? "I can refuse", was the answered thought of my mind30.

I came home with my box and kept it there and went to my other master, the Syrian, at his store and told him that I would like to go home to visit my parents and come back. He agreed and gave me 10 [pounds] to go and come [back] with a full piece31 of cloth to be given to my mother.

I left Kumasi on 10th of August. I arrived at Sandema on 13th August [1956?]. As soon as I came, my father said he would take me to Wiaga to see the girl he had wanted to marry her for me (Parental marriage is traditional in Bulsa). I said: "No, I will not marry until I am about 20 years, before I can marry." But he did not agree. He said to me with angry words: "You must marry before I die. What childish words have you said to me! Do you not know that death always visits you unexpected? Are you sure of your next future? Or do you think if I don't do something for you now before I die, then what can I do for you, as a dead body can't do anything for himself, before [let alone] for anybody else. You must be prepared today so that tomorrow morning I will take you there to see the girl. I have finished with all the greetings32 with the girl's parents and herself. I even said that I would let somebody bring her to you at Kumasi. And now you have come here yourself! That is good!"

So the next day, that was my third day when [after] I [had] come from Kumasi, he asked me: "Let us go to Wiaga!" We went and saw the girl. She was very happy to see me. I gave her 10s. and also 1 to her parents. The parents agreed that we should take her home with us, but my father said: "No, we have to go and come [back] next time." So we came on the same day and my father went again alone and brought her to me33.

I said to my father that I had to go back, for the school will soon be opened. He said: "No, you don't have to go back and leave your wife." At this I was very sad. So I told my wife that I would go to Kumasi and so she should wait for me. I would write a letter to my father with money so that he could let her come to me later. She agreed at first, but when I said she should not let my father know that I was going back to Kumasi, then she was not happy. Then I said I would go to my uncle's house and come back. She agreed.

I took all my books, put them together with some of my dresses in my handbag and went to Kalijiisa [to] my uncle's house. From there I walked by foot again to Navrongo. At Navrongo I did not get a lorry an that day. So I stayed there and the next morning I got a lorry to Bolga. At Bolga I got a lorry straight to Kumasi. The very day I arrived [at] Kumasi I wrote a letter to my father that I was very sorry to leave him and my wife, but I must [had to] complete my school. That was why I had to leave like that. His reply to my letter was that my wife had married away [i.e. another man] and had gone to Kumasi. He said that I had refused her. So she had to marry someone who loved her. [Father’s reply:] "I have done my best to get a wife for you, as a father should do for his son. That is the natural love that I have done for you, but you did not deserve it. So nothing I can do for you in my lifetime before I die," He finished these unhappy words and at the end of his letter he said: "Now try to look for your wife at Kumasi there, If you have found her with her husband write to me at home and I will help you to get back, because her parents were not happy at all when she married that man. The man comes from Wiaga-Chiok. Try your best to look for her, for she loves you very much. So I hope she will come back to you if you see her. May the ancestors and God the Almighty be with you and help you to get your wife back." That was his prayer to end his words in the letter on 7th September 1956.

I heard from my relative [in Kumasi] that my wife had come to Kumasi alone staying with one of her brothers and was asking of [for] me. So I should try to go to Sarbo Zongo to look for her.

In the same week I had a letter from my master, the teacher, who [had] left for U.K. In his letter to me he was still giving me the advice that I should try to complete the school. He posted me a [pair of] shoes and money, 5 pounds.

I did not go to Sarbo Zongo to look for my wife, because time was very limited to me. After school I had to go to the club and on Saturdays I had to go to the club, also on Sundays.

On 25th September, which was Sunday afternoon, I was going to the club with [the] municipal bus and it stopped at Kajartia34 to take some more passengers. They were queuing and in the queue there stood a girl with a brown pancket [packet?] on her face [head?]. She lifted up her eyes to glance in the bus. There our eyes just met. She spoke: "Ah, is it you, the runaway boy?" She paid for the ticket and came into the bus and sat [down] on the same seat with me and said : " Noi mar kala, Achali-ne-kan-jamoa35? That is: May I sit with you, Mr. Running-away-and-never-coming back? "I laughed and said: "Yes, you can do so. Where are you going?" She asked [answered] me: "I'm going to Suame36" That was the name of the place where the club is. "How did you come here?" I asked her. "How do I come here? You think you are the only man who could come to Kumasi and nobody could come? The road is there for everybody and not for you alone." - "Yes, I know that the road is for everybody and not for me alone, but what I want to know is this: whether you came with somebody or [whether] you came alone." - "Well, you did not want me to come with you to Kumasi, but somebody would like me to come with him to Kumasi. So I did come with somebody to Kumasi," was her answer to me. "Where are you going now?" I asked her, " I am going to the slaughter house to collect some meat for my brother, who is working there," she answered me. "Did you come with your husband to Kumasi here?" I asked her. "No, I left him at Koforidua. He has no job to do and has no room of his own. So I found it difficult to stay with a husband as jobless like him37.

At saying this the bus arrived [at] our station and we alighted down. I gave her 10s. and I showed her where I was working and asked her if she would like to have a look at my working place so that any time she wanted to pay me a visit she could visit me there. She thanked me and said: " May I come with you now to have a look at your work place?" I said: "Yes, you can do so if you want." And then she came with me into the club, It was very nice with fine chairs, arm chairs. The floor was well polished and electric fans in all the rooms.

I took her round everywhere in the club, and she was very happy and said: "You have got a better job, but you don't want me to enjoy it with you. So let me go to collect my meat and go home." I said to her: " You go just now, and I will come to your brother to see him and talk to him. Did you tell him about me when you came to Kumasi here?" - "Yes, I did, but he said he never knew [saw] you at all and the [relative] of yours, by [name] Akanguaba. He never heard nobody's name like that in Kumasi here," she said. And I said: "Yes, I am not popular here, because I am always attending school at Asawasi and after school I have to go to work. I will not close in time, always close very late and go home to sleep. So not any Bulsa man knows me here apart from my relative."

And she went away. As she was going away, I began to think, what to do; whether to bring her back as my wife or to leave her and complete my school. And at last I thought of my father's words to me in his letter. And at last I thought I must bring her back to be my wife because of my father's words to me. The very attracted [?] word to me from my father was the word that nothing else he could do for me in life, as a father loved his son and could show his love towards the son. And I again thought of my master's words to me, that is the teacher before he left to U.K. All these problems were very topic to me, but the conclusion of it ended like this: I must bring that girl back again to be my wife.

So on Monday afternoon I went to see the girl's brother at his work place. I met him at the butcher's house. I introduced myself to him and told him that I was the husband of his sister, by name Asuwalie. My father married her for me at home. When I went on leave and my leave was getting over and my father did not agree that I should come back to Kumasi, so I had to leave without his knowledge. I did not tell my wife either before I left Sandema. So later on I had a letter from my father that my wife had married somebody from Wiaga-Chiok and came to Kumasi, so I should try to get her back. And now I have seen her at Kumasi here and she said that you are her brother. So I went to know whether it was the truth that she has told me."

"Yes," said the brother, "she was telling me about you and I said that I don't know you, neither did I ever see you anywhere in Kumasi here. Anyway she is at my house and many people have been coming there wanting to marry her. But she did not tell me whether she would like to marry or not. All she always spoke about was about you and your father: how kind [a] man your father was to her at home and also to her parents, that is my father and mother, because we are from the same mother and father38. But only you, she said, that you don't like her, but you cannot say that to your father. That was why you ran away and left her for your parents. And as she is still a young girl, she would not let any young man [of] the same age with her object [reject?] her like that. That was her reason to marry the Wiaga-Chiok man and come to Koforidua. This is what I have been hearing from her. You can come to my house and see her to hear what she has to say to you39."

That [was] what my brother-in-law spoke to me and I gave him 2 pounds to buy some drink40 and I left him and went back to school. I was late and was punished about [for] that. After school I went back to the club and it was raining. So many people did not come to the club and I closed early about 7.30 p.m.

I went to the house of my brother-in-law straight from the club. There I met the girl with other people, and my brother-in-law asked me to come and sit with him in his armchair. I did so, and he sent for some beer for us to drink. When the beer was brought I told him that I didn't drink at all. He said: "Why?" - "Because I am still a school boy. How much are these two bottles of beer?" I asked him. "They are 5s.," he said, and I gave him 10s. After he had received the money from me he got up and called his sister, that is my wife. When she came he asked her: "Do you know this boy?" - "Yes, I do know him," she answered him. [Brother:] "But why was it that he [Andrew] came here [a] long time [ago] and you didn't want to come out and welcome him?"

[Girl:] "I was sorry! It was because of some people [who] were talking to me41." - [Brother:] "Who were those people? Since you came to me here those people have been coming here. They never tried to greet42 me or ask me something about you, whether you are my wife or my sister. This boy came to me at my work place and greeted me asking me about you. He came to my house here to greet me. You , this small girl, you don't try to think twice at all. Well, now I have nothing to tell you about this boy, because you have married him at home and you left with another [husband] and came here. You have met one another [again], so it is up to the two of you to decide what you want and I shall support you."

During this long speaking of my brother-in-law the girl sat down and said: "In fact I loved him and I married him at home, and I thought we would stay together for some time. But he left me and went away. So I thought that he did not like me. That was why I just left like that and went away. So now I can't say anything whether to go back to him or not."

And my brother-in-law said to me: "What do you think now? You have heard all what [that] she said." I said that it was because of the schools [which] were reopened and my father did not agree that I should continue my schooling and I did not want to stop school. That was why I went away without telling anyone of them, that I was going away."

My brother-in-law then said: "You married each [other] at home as a parents' agreement. So I think it is better to get your wife back, for she still loves you and [I] hope you love her as well. So you can take her home with you." I agreed to his decision and thanked him: "Now I have no room of my own and as such [therefore] I beg you to let her stay here with you until I get a room of my own and I shall come to take her with me. But I have to give her chop-money43 and clothes here with you, if only you will agree with me on [in] this way." That was my suggesting to my brother-in-law, and he said: "I will agree with you on [in] that way, but as you know that many people have been coming here after her [courting her], so if you leave her with me here still people will think that she is still a daughter44 and will be loving her. So I think it is better you take her to your relative." I said: " All right, but I have to see my relative first, before I come for her."

Then we ended off these suggestions, and I asked my wife to see me off at the road side. It was about 10 p.m. I gave her 1 pound and begged her to wait for me. I would buy a cloth and bring it to her the next day. She agreed and laughed.

Then I went away by taxi to my relative. I told my relative about my wife, how her brother and herself have agreed that she should come back to me and what my brother-in-law had said. "So please, relative, if you will let me bring my wife to your house until I have got my own room that I shall [can] take her away." My relative agreed.

So the next day I went to school and at noon I went to my master's [the Syrian's] store and told him the story and asked him also for cloth that I wanted for my wife. And he said I should look for the cloth that I wanted and take half [a] piece45 of it. I chose one and took [it] to my wife, before I went back to school.

I was in the classroom, when my relative called me to come out to see him. When I came out of the class he said that some people had taken my wife away46, and she ran away and was asked of him, my relative's house [?]. So a woman, related to his [the relative's] wife brought her [back] to his house. That was [what] my relative said. I said: "Thank you, but I cannot come now to see her after school. I have to go to the club. So I will come in the evening time." And he went away.

At the weekend I got a room at Bantama [suburb of Kumasi]. That was 24th of October 1954 [1956?], and I took my wife there. Now life was very difficult for me, as I had married at the age of 12 years47, I could not continue my school any longer.

I wrote a letter to my father that I had got my wife back. "Thank you, father, for your prayer to [for] me." I said to him in my letter that I would stop [school?]. I did not receive a reply from him until the end of November [saying] that he had not been well, but now he was better. So if I got a leave I should come home with my wife.

In December I went on holidays and did not go back to school. So I stopped the school in 1956 at the end of the year. At the end of February [1957?] I asked my wife to go home to see my father's condition, how he was, and come back. She went home and my father wrote a letter to me saying that I should come home myself. I wanted to go but there was no money for me to do so. So I didn't go. On the 7th of August [1957] I had a telegram that my father died on the 5th of August 1957.

I took the telegram to my master at his store, gave it to him and he read it and said: "Sorry, Jack! Your father is dead, what a sad news. What do you want to do now, Mr. Jack? Do you want to go home or when would you like to go?" - "Now please, if you will let me," I said. "Yes, you can do so if you want. I will give you your pay if you want it. Yes, please, do you want it now?" he asked me again. "Yes," I answered.

He then pulled his table drawer and took the money from it, gave it to me and said: "Here you are. Your salary is 6 pounds." By then he had increased me [my salary], when I had married. "So I have added 6 to it for you to enable you to go home and come back with your wife. I give you two weeks to come back." I knelt down and got the money. "Thank you, sir," I said and then I went to my relative and told him about the death of my father, I also told him that I had obtained leave from my master, so I had to go today, [I told him] that [it] was two months' salary that I had got from my master.

I left on that same day and I arrived at Sandema on the 10th August [1957] about 2 p.m. I spent only three days at home and I went back together with my wife. We arrived at Kumasi on the 17th of August. I then started work again on the 18th. All this time was tedious to me.

ATTACKED AND INJURED BY ROBBERS

Ghana became independent on March 6th, 1957 and at that time there were different parties in Kumasi. So there was war around the Kumasi area. Many people were killed every day and every night and it had been announced that everybody should be curfewed, that is everybody should sleep at 6 p.m., and I had to close late at about 8.30 p.m. or later than that. So on Monday 20th March at 10 a.m. I was coming to the town from the club. I saw that many lorries were running from the Kajartia [Kejetia, centra market of Kumasi] to the north side and many people were crowding at the Kajartia and policeman. People had guns and bottles were thrown [at] each other and the guns were fired. So I stood about a hundred yards away from Kajartia. There I saw three men running towards me with sticks in their hands wanting to beat me. Then I started to run and they were running across [after?] me.

I came to the roundabout. There were many people and I couldn't run any longer, because there was no way to pass and they threw a broken piece of a broken bottle at me. O my face, on the top side of my left eye the bottle pierced and went very deep, about 2 inches and I fell down. I got up, blood was running down and my eyes were covered with blood. I couldn't see any longer. I removed my shirt to clean the blood from my eyes so that I would be able to see. The blood was too much that I couldn't clean it off.

I walked to my master's store, but the doors were closed. I could hear people talking inside. So I knocked [at] the door and he said: "Who are you?" - "I'm Jack!" I said, "open for me." He opened the door halfway to see who I was. He saw me with blood all over my body. He than quickly came out and took me with his car to the hospital. At the hospital there were many wounded people. I was admitted there for three weeks and discharged.

Again I was coming from the club. It was night, about 9.30 p.m. I met four people an the road and they stopped me, asking me: "Where do you come from?" I was quiet because of fear. They spoke Twi and Hausa. I did not answer them, but they started searching my pockets to get money. These people were murderers. They removed 4s from my pocket and one of them said: "Let us kill him!" The other one said: "No, let us beat him!" The third one said: "No, we have to kill him." The fourth one said: "No, we should beat him." Then they started beating me. I fell down and they ran away. After [that] I lay down for some time to gain back my energy. I woke up [and] started to run, but I couldn't do so, because I was very weak with this beating of four people.

So I was walking step by step, I came to the roundabout near the hospital. Then I saw a dead body lying there at the roadside and there came a police van. It stopped near me and the police came out of it [and] started asking me, where I came from and who had killed this man. One of the police[men] was a friend of my master. The Lord was with me and he came for [to?] me. He had saved me from these four people and he was going to save me from the police. So the policemen wanted to arrest me. But God loved me, so there was somebody to save me. The other policeman, the friend of my master, said: "No, don't! I know this boy. He is working at the Syrian National Club and he never closes in time." The other police[man] asked me: "Who killed this man and what makes your face swollen like that?" I said: "I was beaten by four murderers just now on this road. They have taken my money and beat me and started to run away going to Kajartia." The policeman, the friend of my master, said to me: "Go quickly to your house and tomorrow tell your master that he should let you close in time before 6 [o'clock] p.m. And then they went away.

I came home and asked my wife to get me hot water to clean my sore. She asked me: "Sores? How did you get sores?" - "I was beaten," I answered. "Oh, dear! What is all this? Oh!"

The next morning I went to my master and told him of what had happened to me yesterday, and he took me with his car to the hospital again and I was given an injection of penicillin, 24 ccs daily for eight days. I told my master of what his friend, the policeman had said to me and what he had done for me. "So please thank him, when you see him," and he laughed and said: "You have to thank God, for it was God who saved you from the innocent death." I said: "Yes, it is true."

At the end of the year 1957 my wife was under pregnancy and I asked her to go home48. So she went. When she came to Sandema she wrote to tell me that she would like to come back to me, because my mother and other women were troubling her too much. They did not allow her to eat any good food at all49. So because of this she had never been well at all. So I should post some money for her to come. I agreed with her and posted the money for her to come.

She came back to me in July 1958. She stayed with me in Kumasi for two months, and I asked her to go to one of my brothers, a policeman at Bibiani, to deliver there. That was her first pregnancy and she went there. She delivered on 20th October, 195850. On Monday afternoon my brother made (sent] a telegram to tell me of my wife's delivery safely [safe delivery]. She had brought forth a boy51.

She had stayed with my brother for two months, and I went and brought her to Kumasi with me there.

CARETAKER AT AKUSI

My master, the Syrian man, went home and somebody took over the club. That man was bad to me. He reduced my salary52 and said that the work is not hard enough, and as a new man [that] he is, he had been asked to pay all the labourers in the club and the storekeeper. So he found it too much for him. So he had to reduce our salaries. That would enable him to pay us regularly. I said: "If that is the case then I have to leave the work, because as a married man [that] I am, I can't live on a small salary like that. I can't keep up with that." So I told my wife that I would resign the work, because my salary would be reduced. And she said: "And what will you be doing then? Or will you be going home? It is difficult for us to stay at home. My mother-in-law is not good like my father-in-law. He was very good to me, but he has died. So it is better you carry on with your work until you have found a better job. Then you can resign." And I said to her: "I will go to Accra and find a job there, but first I will let you go to my brother at Bibiani and if I have found a job at Accra, I will let you know by writing and you can come there." And she agreed.

So I went to Accra at the end of December 1958. Before I resigned from the club I asked for a resthouse-money [money for the journey] from my new master and he gave me. From Accra I went to Legon to visit one of my friends, who was a steward there. He took me to the professor, a Scotsman, and he asked me, if I wanted a job. And I said : "Yes, if I get a job , I will be very pleased." He said that he would employ me, but I had [to go] to [a] village about fifty-two miles from here. "There is a resthouse and we need a caretaker. As you have been a club servant, I think you can be a caretaker." I said: "Yes!". And I asked him: "What will be my wages or salary?" He said: "It will be 12.10 a month. Do you like it or is it too small for you?" I said: "No, it is all right." You prepare yourself. I shall take you there at 4 p.m. That was the 8th of January 1959.

The name of the village is Akuso and the name of the project there is "The Extension of the University College of Ghana Agriculture Research Station". It had been there before Ghana became independent. So I can't tell whether it was name [known] as the University College of Gold Coast or the University College of Ghana before I went there as a caretaker. It was known as the University College of Ghana when I went there.

As I went [there] I was very well received by the staff there. So I wrote a letter to my brother at Bibiani that I had been employed and so if he thought that my wife was giving him a lot of troubles he should let her come to me. But if not, he should let her be with him there until the end of the month. These were the words of the letter, which I wrote to my brother and my wife, which I could still remember very well:

Dear Brother,

First of all I would like to know something about your present condition of health. I have been employed as a caretaker to the University College of Ghana at Accra and have parted [?] to a village about 52 miles away from Accra. So I have to let you know and extend it to my wife. Please brother, if you think that my wife is giving you a lot of troubles, then you can let her come to me now, but if she has not been giving you any troubles since she had come to you, then you can be patient and let her stay with you until the end of this month, and I will post some money to you to use it by [for] letting her come to me. Please tell her that I have just been employed, and so she should not worry any more but keep on praying for good health for herself and the baby. She will soon come to me. Here I was given a quarters [a flat]: two rooms with a bathroom and [a] kitchen, also [a] latrine, with electic lights around the quarters. How is the baby? I hope he is all right. Thank you in advance. [I] hope all is well with you, brother. My best compliments to you and your friends. Yours sincerely,

A.Jack

Akusi Accra, 12th January, 1959

As it was a guest house, so many officials have been coming then to rest. So I was receiving presents from some of them. So I was [a] happy man at that time. Some of the M.P.'s were coming there to rest with their girl friends. At that time I was not drinking at all, not even [smoking] a cigarette. As a school-leaver I was taught all this in school that cigarette and drink is [are] bad. So I was still keeping on of [with] that prohibited [abstinent] life.

So at the end of January I posted the amount of 9 pounds to my brother at Bibiani to let my wife come to me. I did not receive a reply from him when I wrote him, but I hoped that my wife was willing to come to me as she heard that I had got a job.

On the 7th of February my wife arrived with my friend from Legon who found me the job. He stayed with me that day and left on the next day. My wife told me that my brother had been a good man to her. Only his wife was bad to her. "I was all right all the time." And my wife was very happy.

It was there that Jehova's Witnesses have been visiting us and were preaching the good news about Jesus to us. I was very interested about [in] the good news and I was able to answer all their questions. So they asked me to come to some of their meetings. It was through these meetings and their conducting that they considered that I was perfect, and they wrote a letter to their headman at Accra that I should be appointed a Kingdom Ministry [Minister?]. I received a letter from the head office of the Jehova's Witnesses at Accra that I had been appointed a Kingdom Ministry [Minister?] of Jehova's Witnesses as from the first of July 1959.

Duties of that post [were]: I had to be there every morning afternoon, also in the evening and on Sundays. Every morning I should also go to preach from house to house every day and to go to assemblies every year where [wherever] the assemblies were to be held in Ghana, [I should do it] for one year. If my ministry had been well, I could be allowed to go [to] other assemblies outside Ghana.

I refused that post, because my job was a caretaker, and I could be wanted at any time of the day or night in the Guest House.

I was receiving letters from home that I should come home, because they wanted to perform the funeral of my father. And my replies to these letters were that I had found a new job and I was not yet due for leave. So I could not get the chance to come and so they should perform the funeral without me. And my mother wrote me a letter saying that she would go away from [my] father's house after the funeral had been performed and so any time I was coming home I should come to my uncle's house53.

At [in] the year 1960 my wife expected a baby after eight months expectant [in the eighth month of her pregnancy?]. She brought forth on the 11th of November 1960 at Sumanya, the Roman Catholic Clinic, a baby boy again. Her first child was a boy and the second also a boy. After she had delivered I got my leave, only fourteen days. So I said to her [asked her] if she could go home alone with the children and come back, because my leave was too small to go home and come [back]. But she refused. She would not go home alone, because my mother would be troubling her. So I said: "Then we will go home together next year."

So I posted money to my mother, 8 pounds, and told her that I would be coming home the next year, 1961. My mother replied: "Thank you, my son, for I have received the money, but please, come home! They have performed the funeral of your father," said my mother,"and I am now a widow to somebody outside your father's house. When you are coming on leave," she said,"come to your uncle's house. The money you posted to me, I have used it to buy a sheep for you." I replied her letter and told her that my wife had brought forth again and the child was too small to travel with me. So I would not come home now, until the child was about a year old.

I was very happy all this time. At the end of 1961 I had a leave again. I did not come home but spent my leave at Accra. Our first son was 4 years old and was speaking Ga54. He could speak Buli, but he never tried to speak it at all. So I decided that I had to go home, if not he would in future forget of his mother tongue.

When my leave was over, I went back to Akusi to start work. I left my wife behind at Accra. I told her to come at the end of the month. She came to me at the end of the month and told me that one of my brothers had come to Accra and was asking of [for] me. He said to her that he had come to me to find a job for him. But she had told a lie to him: "My husband's job has finished and we are preparing to go home. So my husband went to Akusi to bring all our things there, and he asked me to wait for him in Accra here." These were my wife's words to my brother. And my brother said: "If that is the case then I have to go back to Kumasi. At Kumasi I may get a job to do," he said.

Jehova's Witnesses were still insisting that I should accept the post, because I was a good preacher when we went from house to house to preach on Sundays after our Sunday Services. But still I refused.

BACK AT SANDEMA

At the end of November 1962 I had my leave again. That time I told my wife that we had to go home. So we came home 1962. At home life was tedious to me. I did not go to my father's house as I was told by my mother. I did not go to my uncle's house either. I left all my boxes and bed tables [?] and chairs in the house of my uncle in the town [the centre of Sandema]. My uncle had a house at the town at that time. So I put all our things there before I went to my father's house to greet the people there and thank them for [that] they performed the funeral of my father during my absence.

They told me: "You have to buy drinks for us, because we did everything for you, and you were not here to take part of [in] the funeral's performing. So now as you come you have to buy some drinks for us." I said: "Yes, I will do so, but that will be on market day."

After I had left them, I went to my mother, where she was staying. It was the same [clan-section] Balansa, but not the house of my father. I asked her: "Why was it that you wrote me that I should not come to my father's house?" - "Because your brothers were quarrelling about the cattle of your father55 and wanted to kill each other by witchcraft action. And the first son, your elder brother, said that he knew that you are a clever boy and so whenever you came home, you would take away all the cattle from them. So he was trying to get some juju56 and keep it awaiting you to come. When you came home he would then kill you," said my mother to me. "How did you get to know this," I asked her. "The man whom I am staying with as my husband, he has found out from the soothsayer57. And he met your brother one day with a Maalam58. He was asking the Maalam for something that would kill a person," she answered,"that was why I wrote the letter asking you to come home, because if your brother has got the medicine that can kill a person, he will send it to somebody who will go to Kumasi and may know where you are at Kumasi and come to you to kill you with the medicine. Now as you have come do not go back to the South. I bought a sheep for you and it did well, it bred. They [are] now four, and two goats I took to your uncle's house [at Kalijiisa]. So please let us go to your uncle's house and sojourn there59. Do not stay with your brothers. Take off your hands from your father's cattle. If the almighty God helps you, you will get cattle of your own, because now if you take five sheep you can exchange them for a cow."

That was the advice of my mother to me when I came back from the South. I asked her: "Are the cattle of my father many?" - "Yes," she answered, "they are about thirty and [there are] many sheep and goats," she said. "All right, as I have come, my brothers have not yet told me anything about the cattle. So I will wait and see if they will tell me something about the cattle," I said to my mother. "I will not stay with them, I also will not go to my uncle's house [at Kalijiisa], but I will be staying in the town, in the house of my uncle to see how things are going on," I said to my mother.

And I left her and came back to the town. I was then staying in the town at the house of my uncle60.

One day I went to see my brother at my father's house [at] Balansa. My elder brother called me in [into] his room and told me that:"We performed the funeral of our father during your absence. We have been writing you to come home so that we will perform the funeral and you didn't come. So we performed it. We caught five of the cattle and two sheep and used them to perform the funeral. Now the cattle that are left are about thirty and the sheep also about twenty, the goats about eight. So as you have come I have to let you know." that was what my brother told me in his room61. "Thank you," I said,"I will go back to the south, but not now. At the moment I am staying in the town, because my mother is no longer in this house. So it is difficult for me and [to] come and stay here with you. So I will be in the town, and if you want me for anything at the house, you can send for me to come." I said this to him and left. I came back to the town.

When I came to Sandema there were no Jehova's Witnesses here in Sandema, only Presbyterians and Roman Catholics. So I joined the Presbyterian Church. Their pastor was a Scotsman, [by] name Robert Duncan62. I went to his house to visit him and told him that I was a member of the Jehovah's Witnesses at Akusi, a village near Accra. "I have been baptized there, and as I have come home I didn't find any Jehovah's Witnesses here. So I would like to join your church." He said: "That is good of you . You are a Christian. I am very pleased to hear that you would like to join us. May I ask you a question?" he asked me. "Yes," I said. "Would you like to be my interpreter?" - "Yes, I will ." - "I need an interpreter who will interpret for me in the church and in the schools. I can't speak the Buli language, and I find it difficult to preach." He said this. "But no pay for it, so if you will do it voluntarily." - "Yes, I will do. Is it only on Sundays?" I asked him. "Yes, and also in the Primary Schools twice a week, Mondays and Wednesdays. I will see if I can get some small money for you from my pocket," he said, and I said: "Yes, I will do it for you." - "I will be going to Fumbisi tomorrow morning at 8 a.m. So if you would like to come with me," he said. "Yes, I will come with you, but will I come to your house here or should [I] wait [for] you in the town?" I asked him. "You can wait [for] me at the town." he said and I left him and came back to the town.

The next morning at 8 o'clock a.m. he came and took me with him to Fumbisi. On the way to Fumbisi he asked me: "You are from Sandema by birth, are you?" - "Yes," I answered. "Would you like to become an evangelist?" he asked me. "I can't say yes or no, because I have just arrived home with my wife and two children, and I am not yet will settled," I said to him. "What do you mean by 'well settled'?" he asked me. "What I mean by well settled is this: My father died and my mother left my father's house and married a neighbour of my father at a different house. And when I came back from the South, my mother told me I should not go to my father's house. I should rather go to my uncle's house and I don't want to go there either. So at the moment I am staying in the town with my wife and the children. This is what I mean [by]: I am not well settled." He went on to ask me the reason why my mother had told me not to go to my father's house. I told him half the story that my mother had told me. And we reached Fumbisi. I was working with him voluntarily. He sometimes gave me some money from his pocket.

Sister Doris came [back] from leave. She was then running the [Presbyterian] clinic here, and she had nobody to help her in the clinic as a dispenser. She asked me if I could help her in the clinic as a dispenser with a salary of 5 or 10.00. I agreed to that appointment. That was January the 9th, 1963. Life was very hard for me. She said this to me that she would go to Accra and come back to start work.

A THEFT AND ITS CONSEQUENCES

When I returned from the South I had many dresses, nice ones, 12 trousers and about 16 shirts, they were all expensive ones. As I was in the town, my mother came to join me in the town. On 12th January [1963] my wife went to my uncle's house in the morning. That was Sandema market day. She did not come back and it had got very late. So I said to my mother that I would go to Kalijiisa to see what had been wrong with my wife, because today was market day and she left here in the morning to Kalijiisa. She had kept so long to come back. And my mother said: "You have to find out to know what has been wrong with her there."

So I went. I reached there about 6.30 p.m. and my uncle was outside. He saw me and began to laugh and said:"You are coming after your wife?" - "Yes," I answered him. "I am sorry," he said,"[that] you are coming after your wife." "Yes I answered him. "I am sorry," he said, "when your wife came here, I asked her to wait, for I wanted to give her some rice, but my wife has gone to Chana with the keys63 of my room, but she said that she would come back from Chana in time. That was why I detained your wife so long. Now as you have come, you have to stay the night here with us and you can go back to the town tomorrow with your wife. I will give you food stuff to take with you." And I said: " All right!"

I stayed the night at Kalijiisa, and the next morning my uncle gave us a half bag of rice and also some groundnuts. And we left Kalijiisa going back to the town. When I reached the town I saw my mother outside of the house weeping. "What is wrong with you, mother?" I asked her. "My dear son, all your boxes have been stolen from the room. There is nothing left in the room, only your cover cloth is left. It was lying outside of the room and I took it. [A] thief has come to steal [from] you in the night while I was asleep," she said. I ran quickly into the room to see whether it was true or not. No, what I could find there was only the cover cloth. All my three boxes [which] contained my nice shirts and shoes together with my wife's clothes had been taken away by thieves.

I started weeping and my wife was weeping, too. My books and bibles, all that had been stolen. What was left to us was the cover cloth and the shirt and shorts that I had worn [when I] went to Kalijiisa, also the clothes that my wife wore and [when she] went to Kalijiisa. [These] were the only dresses we had and nothing at all with us.

I went and reported the incident to the police, and they said that they couldn't do anything unless I was able to get the thief. But how and where could I get the thief? I left the police station and came home with my worries.

In the evening the pastor came to me. He saw me still weeping and he asked me: "What is wrong with you?" - "All my boxes, three of them, containing our dresses and books have been stolen last night," I said to him. "Oh," he said, "did you report the case to the police?" he asked me. "Yes, I did." - "And what did the police say?" he asked me again. "They said that they couldn't do anything unless I myself was able to get the thief or if I knew him. Then they would go and arrest him, but I don't know the thief, neither do I know where he came from." And he [the pastor] said: "Come with me. I will take you to my house and bring you back. Call your wife to come, too," he said. And I called my wife.

He took us to his house. He told his wife the story and the wife said: "Sorry, very sorry, Andrew." She brought some tea for us with some cakes. The pastor said: "Mr. Andrew, we will pray for you and your wife . And I will tell my congregation to pray for you. Do not weep any more. But remember what Jesus said in the bible: "Do not worry about the clothes and food you will eat today and tomorrow, but first of all seek the kingdom of God and all that you need shall be added onto you.' So as a Christian [that] you are I will advice you not to worry, but keep on praying, and I am sure, God the almighty will answer your prayers and will give you something to wear. Then I said: "Thank you, pastor." And he said: "Let us pray!" He started to pray: "Oh Lord Jesus, hear us as we pray for this our brother and sister! Almighty God, and we give you thank for our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, And we ask you to help this our brother and his wife. For they are in many worries and unsteady of mind, because all their things have been stolen and they have nothing to wear. We do remember your word to us that we should not worry about the clothes and the food we will eat and wear. Look at the birds. They do not work, but God cares for them, how much more we [for us] human beings. So God Father, help us to keep this your word and listen to whatever you tell us from the bible. Oh God, hear us! We ask you in the name of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ. Amen."

After his prayer we drank the tea, and he moved from the chair and went into his room. He called his wife to come and she also went into the room. They brought 10 pounds and some old dresses of his wife and gave the money and the clothes to us. I received the money and the clothes and thanked him. He again went back into his food store and brought some food stuff and a box of oil, the American supplies. The box contained 6 gallons of oil and [he] gave them to us. I thanked him again and said we would go home now and he took us and the things he had given us back to the town.

After I had come to town and I could not find the things in my room as I used to see them, I was weeping again and a friend of mine came to me because he had heard what had happened to me and he advised me to go on drinking and that would help me to forget the losing of my property. I took his advice and he even bought the drinks for me on that day. That went on for about two years (1963-65]. I always became mad whenever I was drunk.

And my wife was annoyed with me. She said: "If you want to live on a life like that, then we cannot keep up with such a life. That proves nothing better future at all for us [proves that our future will not be good]." After saying these words to me she went to her father's house. She did not come back for three days. so I went there after her to find out what was wrong with her there. When I went [there] I saw her and her mother. As soon as her mother saw me, she ran quickly to her daughter and said to her: " Do not go with your husband whatever he tells you. Do not believe him, for I will not let you stay with him again as a husband. It was because of your father-in-law's kindness that you have married him. Now that your father is not alive and your husband is poor, I will not agree and let you continue marrying him. You have to give him his children and marry somebody else, who will be able to look after you proper[ly]. All your nice clothes have been stolen. I am sure that journey [new?] husband will buy them for you. Please, take this advice that you will not go with your husband again, when he asks you. But do not say to him that I have advised you on this. Tell him that he should go home alone, and you will follow him later on in two days' time64."

After she had finished saying these words to her daughter she came out and said: "My son-in-law, your wife is in the room. You can [come] in to see her. I am going to Siniensi and I will not come back today. So after you have greeted your wife you can go home and leave her to take care of my room until I come back from Siniensi that I will let her come to you." She just spoke these words to me and left. I called her back: "Please, will you let me ask you some question about my wife?" She answered: "Yes, you can do so." - "Please, Mother, my wife left our house and came here without telling me that she was going to her father's house since [for] three days today. And I was wondering why she should do this. There had been no matter between her and me. So may I please know from you, whether she told you something against me, when she came to you?" I asked her this question.

"No, my son-in-law," she answered, "your wife did not tell me anything about you. All she said to me when she came was that you are getting mad, because of the losing of your nice dresses and books, for you will never get them again in your life. So whenever you think of your dresses you are not happy and even start to weep again. And a bad man always comes to you giving you wrong advice that you should go on drinking . That would help you to forget all your sadness, and you foolishly agree and have taken his advice [and] started drinking. That was what your wife told me. And to me [as for me], I am not in agreement with you at all. Anyway I cannot advise you on any good life, because I did not know you at first. For you did not come to me and tell me that you wanted to marry my daughter. It was your father who was a kind man. He asked me to let my daughter marry his son who was at the South. And now he is not alive. And you don't seem to like my daughter to be your wife." She went on: "Anyway my daughter did not tell me that you don't seem to like her. I can see it myself."

"How is it that I don't seem to like her as a wife? How did we manage to get children? Or do you think that the two children that your daughter has are not from the two of us by sexual intercourse? Or do you think that she had the children by prostitution65? From what that she had the [You have said] that you don't know me that I am you son-in-law, but it was my father, who was a very kind man,[who] came to you asking you to let your daughter marry his son. Did I not come to you with my father and said to you that I would like to marry your daughter? Please, tell me that I am now a poor man and as such you wouldn't like your daughter to marry a poor man who cannot give you money all the time. Because of that you would like to marry away your daughter from me to a rich man. If you had said that to me, then I would have nothing to say any more, because I am a poor man today to [for] you. But please, note that I did not invite poverty to myself, rather did poverty invite itself to me. I can't help it. It is not dodgeable [possible? makeable?] that I should escape from it. I have to keep on praying to God to see and to hear from him what God has to do for me in the future. If only God gives me [a] long life and I am living a healthy life [and] no sickness or bad troubles such as stealing [and] murder comes on me [I will be contented]. But only the poor [poverty], I have to thank God for that. For poverty is everywhere in the world, not only [with] me that I should [not] be worried very much. You can take away your daughter from me. You have made it clear to me that you don't want your daughter to be with a poor man as a wife to him. I thank you very much for that. I myself do not want to keep somebody's daughter to be suffering so much with me." After I had spoken all these words to her she went away without a word to me.

And I went into the room to see my wife and ask her: "Would you like to come with me or [will] you take the advice of your mother?" She replied: "I have only come to visit her and come back home. I did not say to you that I am no longer married to you. Why should you stand outside talking all these angry words to my mother? Are you drunk this morning?" I answered her: "I am not drunk. It was your mother who offended me. That made me speak these words to her. If you have not taken the advice of your mother, then prepare and let us go home." Then she said: "I have nothing to prepare. So let us go!" And we came home together on that day.

Her mother came to me later after I had brought [taken] my wife from her. She said: "I have come to visit you and to see whether you reached home safely66 with your wife or not and to find out to know whether there is a trouble with you and your wife, because you were very much annoyed with me on that day when you came to visit me and take away your wife." I answered her and thanked her: "Thank you for your visiting us and to find out whether there has been a trouble between us. There have been no trouble[s] between us at all." And she stayed the night with us. I entertained her with drinks and dinner with two Guinea fowls, and the next morning I again gave her another Guinea fowl to take home to prepare food for herself67. And she went away thanking me for the entertainment I had entertained her.

Sister Doris came back from Accra, and the pastor told her about the incident [the theft], and she was very sorry to hear it. She asked me to come to [the] clinic on Monday. So I went. After [my visit to] the clinic she came to my house in the town and gave me 5 pounds and some dresses. I was then working with her as a clinical assistant.